Mutual Fund Fees: What You Can, and Should, Avoid

By: Robert F. Abbott, freelance writer and author

Mutual fund fees evoke a lot of heated discussion. Some argue they cost too much, others vehemently disagree. In this article, I won’t argue one way or the other; instead, I’ll show you examples of the fees, and help you understand them.

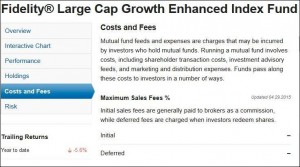

We start with an example fund, the Fidelity Large Cap Growth Enhanced Index Fund (FLGEX). It comes to our attention because it ranks fourth on U.S. News & World Report’s list of best large growth funds (this is not a recommendation or an endorsement, simply an example used as a teaching tool).

Take a quick look at this screenshot from its website:

As you will notice on the right side, the magazine lists several issues that make up mutual fund fees. The easiest way to understand them is to break them into two categories: management expenses and operating expenses.

- Management expenses: The costs involved in managing the fund, which would include the salaries of the fund managers, assistants, and some other staff. As an Investopedia article notes, “The management fee is significant for the fund, because the cost of hiring and retaining the investment team is the most expensive part of managing a mutual fund.”

- Operating expenses: The general and administrative costs associated with any office, including marketing, record-keeping, and the filing of forms. To cite Investopedia again, “While these fees are not directly involved with making the investment decisions, they are required to ensure the mutual fund is run correctly and within the Securities and Exchange Commission’s requirements.”

Together, these two sets of expenses make up what we call the Management Expense Ratio, the MER. For those mathematically inclined, you calculate it by dividing a fund’s total expenses by the net assets of the fund. And more specifically, the published rate reflects the average net assets of a fund over a year.

Sales Fees

Just below the explanation of costs, we see a section titled Maximum Sales Fees %. Here, neither fee applies.

In investing jargon, Initial refers to a front-load fund, one in which you would pay a portion of your initial investment to the company and person that sold you the fund. Avoid front-load funds unless you have an exceptionally good reason to buy them. The upfront fee may not seem that much, but compounded over a few decades will become very large.

Deferred refers to a back-load fund, where you pay a fee after selling part or all of the fund. You may avoid the compounding effect this way. However, from personal experience I can tell about a great drawback of back-load funds: it’s much harder to make a sell/hold decision. That’s because every time you think you should sell the fund, you take into consideration the fee which a sale will trigger. In my case, I held the fund much longer than I should have.

Whether Initial or Deferred, these are the two types of fees you can and should avoid. Paying a sales fee does not mean better performance, it is simply a commission for the salesperson, who in some cases may give you advice. But, advice from such salespeople tends to be biased toward the funds they sell.

Your best bet is to do some fundamental research and buy funds from a discount broker or similar institution. Paying sales fees is harmful to your economic health!

Maximum and Actual Fees

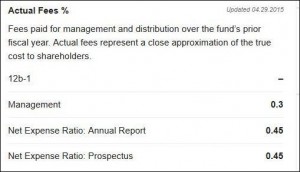

As the screenshot below shows, the U.S. News & World Report lets potential buyers know about the maximum fees that might be charged, and the actual fees that were charged in the previous fiscal year.

For the Fidelity Large Cap Growth Enhanced Index Fund (FLGEX), the fund company has capped its management fee (the biggest expense for most funds) at roughly one third of 1%. They list no maximums for other types of fees, which means, in this context, they do not charge them. Redemption fees refers to a charge that some (other) fund companies charge when you sell their funds; it is separate from and may be added to back-load or deferred fees.

Next, we turn to what the fund FLGEX actually did charge its fund holders in the most recent fiscal year. We see 0.3% again as the Management fee, and a total fee of 0.45% under listings for the Net Expense Ratio. Annual Report refers to what the company actually charged, while Prospectus, refers to the amount the company said it would charge when it created the fund. The company has stuck to its original promise (although I haven’t checked previous annual reports to confirm what happened in the intervening years).

Is 0.45% a reasonable price to pay for this fund? You will need to answer that question yourself as you compare the performance and price of this fund with other funds. Remember that the published performance numbers show you results after the taking off the expenses.

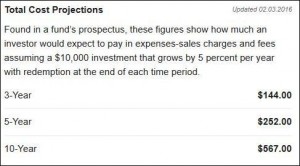

The Dollars & Cents Version of Your Mutual Fund Fees

The U.S. News & World Report coverage includes fund costs in dollars and cents as well as percentages, making them less abstract. Remember that the fees shown apply to the specific scenario outlined in the opening paragraph.

In trying to make the dollars and cents version more realistic, it offers a scenario in which costs are assessed as if they were in a growing fund. Here, the projection shows you would pay $144 or an average of $48 per year for a fund that would have grown to $11,576.25 by the end of year 3. Again, this cost is relative, and only has meaning when compared with other funds.

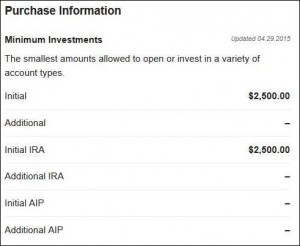

Can You Afford This Fund?

In efforts to keep their costs down, many fund companies set minimum amounts for first and subsequent purchases. Fidelity sets one minimum, $2,500 when you first buy into the fund, but after that you can buy additional units in any amount. Just be sure when buying additional units of any fund that your broker does not charge you a fee for each additional purchase.

Whichever fund you buy, check this information carefully, so the terms fit with your situation. For example, if you want to start with a lump sum and then contribute $100 per month, will the fund company allow you to do that?

Mutual Fund Fees: Conclusion

Mutual fund fees and costs, admittedly, are not an exciting subject. However, understanding them will stand you in good stead as you research and then make your commitments.

Costs do play an important role in what you eventually get out of your investment. It’s not the actual money out of pocket this year or next that will make the difference, but the compounding effect of dollars not put to work.

Next, read about the Mutual Fund NAV